Bhutan, the (Un) Happiest Country in the World: The Mass Expulsion of the Lhotsampa People – Part II

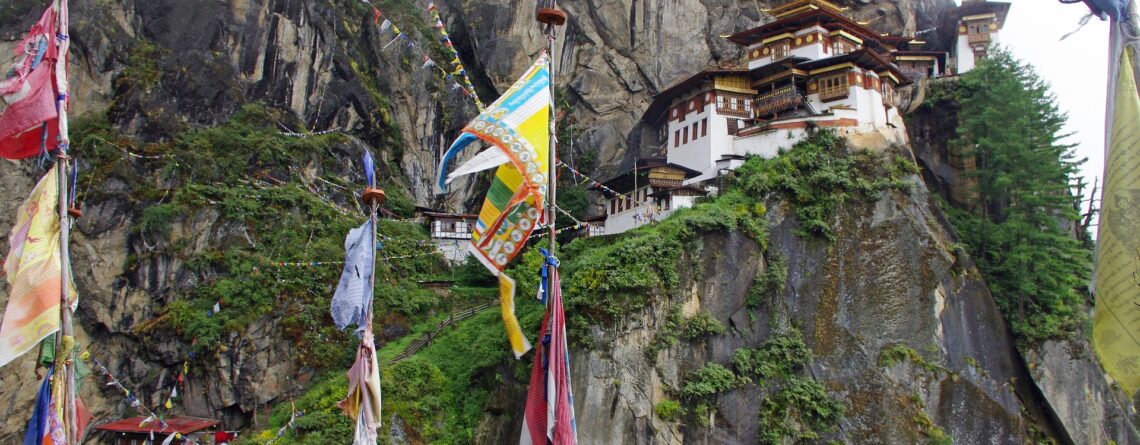

Globally, most people are unaware of the tiny country of Bhutan nestled in between the global powerhouses of China and India. Bhutan has been successful in promoting the image of a peaceful and picturesque kingdom of clouds, a haven from the rush and chaos, a modern-day Shangri La. Its beautiful scenery, rich cultural heritage and secretive nature draw intrepid tourists to explore its hidden beauty. Bhutan often remains a mystery to the outside world and those who do know of it usually associate it with one of two contradictory titles; firstly, the happiest country in the world, due to its unique measurement of Gross National Happiness instead of Gross National Product, and secondly, as the source of the largest number of refugees escaping persecution during the 1990s due to government mandated ethnic cleansing.

This article, the second of three parts, details the decades long habitation of various refugee camps in Nepal. The first article seeks to introduce and explain the origins of the conflict and ethnic tension, and the third article will discuss why this conflict still matters and how it pertains to current regional and global conflicts.

The Lhotsampa Exodus

Whilst the Bhutanese government claims the Lhotsampa people left willingly, there are many claims from the Lhotsampa people themselves which state they were intimidated or bribed into leaving. The Bhutanese government cites the numerous ‘Voluntary Migration Forms’ (VMF) that stated that the person in question had left Bhutan voluntarily and included provisions which called for the surrender of key identification documents to the government. The government even videotaped testimonials from various ‘emigrants’ wherein they stated they were not being coerced or threatened to leave Bhutan and their choices were completely their own. Later those same ‘emigrants’, now refugees in Nepal, released a joint statement that they were indeed forced out of Bhutan. They declared various reasons for their forced evictions:

One claimed that he had been served with a notice to leave Bhutan because his older brother had already left, others said they had been told to leave because they were unable to produce certificates of origin (because their relatives had left Bhutan and taken such documents with them), one because his brother was an 'anti-national’, and so on. They said that they were told collectively to leave their houses on 25 March and gather in Samchi town… (Hutt, 1996)

The Bhutanese government maintains that those in the refugee camps in Nepal were “illegal Nepali residents in Bhutan; imported Nepali labourers who were claiming to be Bhutanese nationals by virtue of having worked in Bhutan; dissidents, many of whom had committed criminal and terrorist offences in Bhutan; Bhutanese nationals who had emigrated legally after renouncing their citizenship and selling all their properties; and people from other parts of the region, including Nepal itself, who had never even set foot in Bhutan.” (Royal Government of Bhutan, 1993). Such statements by the government of Bhutan have encouraged the narrative that those who had left Nepal had both done so willingly and in support of the resistance movement concentrated along the border and in Nepalese refugee camps. This assertion is widely contested by scholars who maintain that the Lhotsampas who were mainly rural agriculturalists would not abandon their land to show support for a movement. They point to other such movements which have mainly been led by the educated urban class and has had trouble mobilizing support in rural areas. Even so, the Bhutanese government has effectively barred the Lhotsampas from returning as they have discredited the refugees themselves, as criminals, illegal immigrants and voluntary emigrants, and discredited any existing identification cards as forgeries. Even if the refugees could prove they had the right to return, it would be difficult to do so as their previous land and property has been given to other Bhutanese citizens.

The Himalayan Refugee Camps

The flow of refugees from Bhutan into Nepal started in the 1990s and continued for the next decade. In 1992, there was an estimated 600 refugees arriving in Nepal per day, with that number decreasing to smaller groups in the following years. As of 2007 there was an estimated 107,500 refugees distributed among 7 camps in eastern Nepal run in conjunction with the Government of Nepal and the United Nations Commission of Human Rights. Whilst the Bhutanese government cites the Nepalese Refugee Camps as having a much better quality of life than one would have living as a citizen of either Nepal or Bhutan, experts disagree. Though the camps have been much improved upon they were at many points plagued by measles, cholera, tuberculosis, malaria, diarrhea, beriberi and scurvy and there were very little opportunities for growth, employment or any forms of productivity for their residents. Human Rights Watch reported that, ‘the Bhutanese refugees in Nepal are trapped between their forced dependency on international assistance and the increasing reluctance of the international community to keep providing for their needs’ (2007, 18–19). In 1993, bilateral talks between Bhutan and Nepal began to discuss the possibility of repatriation. The talks were largely unproductive until seven years later when there was an agreement between the Bhutanese and Nepalese Governments to create a Joint Verification Team, which would sort the refugees into one of four categories; genuine Bhutanese Citizens who were forcefully expelled and thus would be able to return to Bhutan, those who had signed Voluntary Migration Forms, therefore sacrificing their citizenship and rendering them ineligible to return, those who were considered non-Bhutanese nationals and those who were Bhutanese criminals, who would also be ineligible to return. In 2003, the results of the Joint Verification Team who had surveyed just one camp were published to much controversy. The team had found that only three percent of the camp inhabitants were eligible to be repatriated, and the rest had fallen under the categories of voluntary migrants, non-nationals or criminals.

Those who were considered eligible were set to be repatriated in October of 2003, however due to the camp residents attacking the Bhutanese representatives the talks were called off. The reasons for the attacks differ depending on who you ask, some think that they were the result of the representative provoking the crowd, and others insist they were premeditated by the refugees.

This event lead to the complete breakdown in talks of repatriation between the two countries and the refugees were left to exist in limbo reliant on international assistance until a solution was found.

Dodaj komentarz